The story of indoor air quality through the COVID-19 pandemic and the road ahead

The importance of indoor air quality is among the key lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Pre-pandemic, much of the focus in the area of air quality was on the outdoor environment, but as COVID took hold and it became clear that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was airborne, indoor air quality moved to the forefront of the public consciousness. During the early stages of the pandemic, more information came to light demonstrating the critical role filtration had to play – from facemasks to HEPA filters to air purifiers, etc.

The initial stages of alarm during the pandemic gave way to a certain level of filtration awareness and a better understanding of filtration systems and how they can be optimized to protect against virus spread. It was evident that, at a minimum, the installation and operation of filtration systems needed to be improved to ensure indoor air quality, and in many cases the filtration systems themselves required a certain level of improvement to protect against the virus.

So, the question in considering the way forward for indoor air quality in what hopefully will soon be the post COVID-19 pandemic era, is: What can and/or needs to be done to better prepare filtration systems for the next airborne pathogen to take the world by storm?

Current state

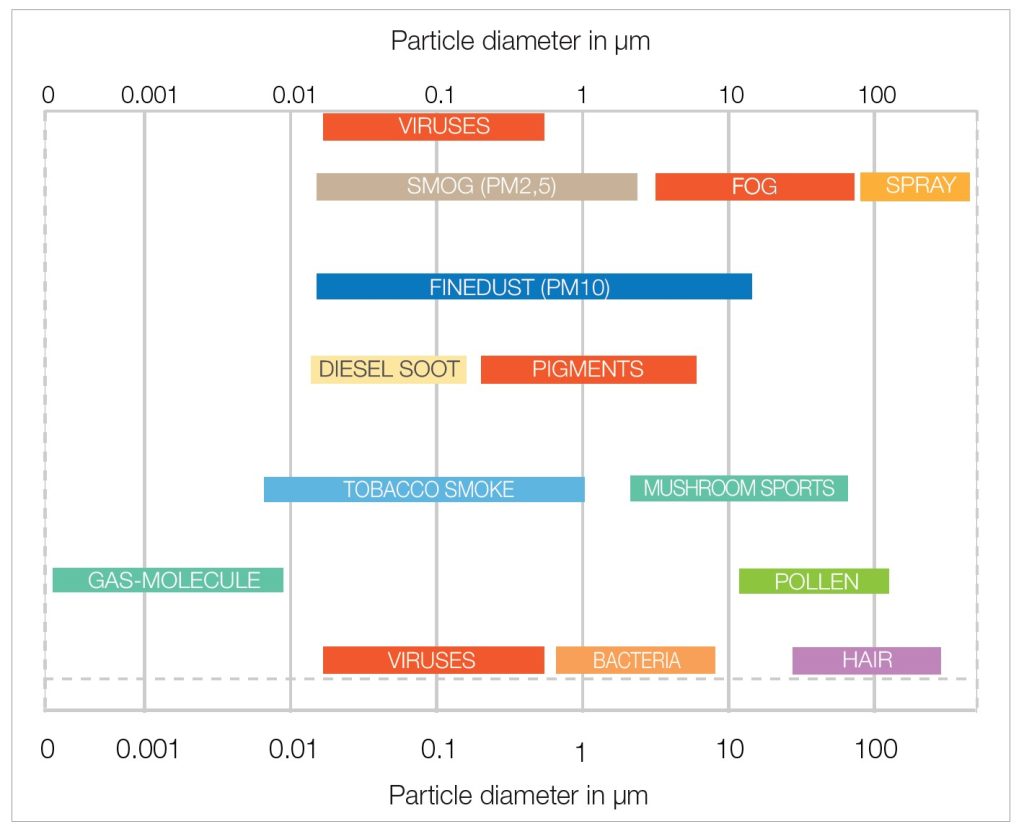

According to much of the currently available scientific research, there is overwhelming evidence that aerosols play an important role in the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Generally, an aerosol is defined as a suspension system of solid or liquid particles in a gas. An aerosol includes both the particles and the suspending gas, which is usually air.

Aerosols are typically classified according to their physical form and how they were generated. Fume, mist, smoke, smog, diesel soot or fog are typical examples.

Viruses, like SARS-CoV-2 become airborne by attaching to aerosols and riding along with them. All accumulations of aerosols in the air to which fungi, bacteria, pollen or viruses adhere are called bioaerosols.

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) May 2021 brief on SARS-CoV-2 transmission, the principal mode by which people are infected with SARS-CoV-2 is through exposure to respiratory fluids carrying infectious virus. Exposure occurs in three principal ways:

- Inhalation of very fine respiratory droplets and aerosol particles;

- Deposition of respiratory droplets and particles on exposed mucous membranes in the mouth, nose, or eye by direct splashes and sprays; and

- Touching mucous membranes with hands that have been soiled either directly or by touching surfaces with virus on them.

In the U.S., the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Epidemic Task Force has issued a recommendation for a minimum of MERV-13 level filtration in all indoor commercial and residential environments. MERV stands for “minimum efficiency reporting value.” MERV 13 filters are recommended because they can effectively filter 1-3 um particles, the range where virus-laden aerosol particles have been determined to be of most concern.

While regular air filters are not designed to prevent the spread of viruses, they are essential in minimizing the risk as viruses tend to attach to airborne particulate matter and aerosols. Thus, regular filters with a high filtration efficiency (MERV 13 (ASHRAE) or ePM1 (ISO)) are crucial to reduce the risk of diseases transmitted through the air. HEPA (High Efficiency Particulate Air) filters are mandatory in most critical environments, such as hospitals and healthcare facilities (though some only require MERV-14 in certain spaces) and can also be recommended for use in medium-risk environments like airports, schools, etc.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic and evidence showing the potential for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to severely affect the elderly and people with existing medical conditions, Eurovent has recommended HEPA filters in all facilities designed to support, help, house or care for these groups.2 Similar recommendations have been made in the U.S. and other parts of the world struggling to protect their most vulnerable people from the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

ISO’s COVID-19 guidance recommends maximizing the amount of outdoor air and room air changes through ventilation systems (with appropriate filtration and duration of operation), turning off air recirculation systems, and keeping doors and windows open to the greatest extent possible.3 ASHRAE’s Epidemic Task Force is more nuanced on outdoor air and only recommends an increase if temperature and relative humidity can be maintained.

Problem areas

In general, HVAC systems that are recirculating the air can play a crucial role in the spread of virus within a building, if virus-laden aerosols are not removed from the air stream. With a given air change rate of approximately seven times per hour (based on a 5.500 m² building with AHU operating at 12.000 m3/h using a bank of four 600×600 filters with an avg. airspeed of roughly 2,2 m/s.), living viruses (assuming three-hour lifetime) can be carried by aerosols and circulate 21 times and spread throughout the building within the ducts.1

The potential negative impact of recirculation was a revelation for many during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it highlighted the importance of proper operation of HVAC systems to protect against the spread of virus, as well as other harmful, indoor airborne contaminants.

“For most of the installations, the use of existing technology can assure the IAQ,” said Marco Adolph, managing director for TROX North America LLC, a leading provider of air conditioning and ventilation systems. “The critical aspect is how to get all pieces together. In the end, it is more work at the design and consulting phase. The correct installation and maintenance also play an essential role.”

Inherently, filtration within commercial and residential HVAC systems is designed to protect the equipment, not the people, within a given facility. That said, HVAC systems can be operated to provide adequate protection for people as well, but proper operation is key. And the SARS-CoV-2 virus showed how different variables in the environment can require a rethinking of the standard operating procedure for HVAC systems.

“COVID-19 changes the way we look at indoor air quality from the perspective of filtration,” said Ing. Wim H. Fekkes, manager of research and development in Europe, for AAF International, a global specialist in indoor air quality. “Originally the air outside had to be cleaned to refresh the indoor air with centralized systems. With COVID-19, these centralized systems also provided a mechanism to spread the virus, so it became important to filter the recirculating air instead of the outside component only.”

While ASHRAE’s Epidemic Task Force has recommended a minimum of MERV 13 filters for all indoor environments during the pandemic, MERV 13 (or ISO ePM1 equivalent) filters by no means guarantee an appropriate level of filtration to protect against virus spread.

Wade Conlan, commissioning and energy manager for Hanson Professional Services, Inc., and a participating member of the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force, said that MERV 13 is only a rating, and such filters require the appropriate installation and maintenance to provide the desired filtration within a given facility. Further, he said not all systems are designed to support MERV 13 filtration.

Fekkes agreed with this sentiment. “Originally, filtration [in HVAC systems] was there to protect the mechanical parts and clean the fresh air, but now higher requirements are made,” he said. “Most HVAC sytems are not well designed for the higher demands of better filtration. You cannot necessarily just put a better filter in a current installation.”

Conlan pointed to U.S. schools as a good example of a problem area when it comes to maintaining a minimum of MERV 13 filtration. A June 2020 report by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) estimated that 54% of public school districts need to update or replace multiple systems in their school buildings, with HVAC topping the list. Forty-one percent of districts need to replace or update these systems in at least half their schools — totaling roughly 36,000 schools across the country.4

According to a recent report by the National Education Association, educators have been sounding the alarm about “sick” schools for years, if not decades. According to a recent NEA survey of its members, only about one in three report that adequate ventilation has been implemented in their schools. Members in higher poverty schools are less likely to have adequate ventilation. When directly asked whether they think their school’s ventilation system is providing them enough protection from COVID-19 to feel safe working in-person, 34 percent said yes, 38 percent said no, and 28 percent said they weren’t sure.5

With many schools housed in facilities that date to the 1950s or 1960s, they are incapable of supporting MERV 13 or ISO ePM1-level filtration and, further, aren’t designed to provide adequate ventilation to ensure IAQ.

Don Donovan, the president of Camfil EMEA, a leading global manufacturer of premium clean air solutions, said that, beyond the virus, attention must also be paid to the harmful off-gassing that occurs in many indoor environments from, for example, carpets, photocopiers and flat screen televisions, to name just a few sources. In many cases, he said these contaminants pose an even more troublesome concern for IAQ, as HEPA filters aren’t able to filter gases, and molecular-level filtration solutions will be required to effectively mitigate the threat of off-gassing.

While the move toward a higher level of filtration and establishing more best practices in the area of ventilation and air changeover rates is a step in the right direction, Donovan said regulations along with more strict monitoring and enforcement will likely be required to make the impacts necessary to address some of the bigger IAQ challenges in the long term. For example, he said schools are an obvious area of need, but they are not funded, in many cases, to make the improvements necessary to provide the necessary air quality to protect students, teachers and others in school buildings.

“Everybody’s talking about IAQ now, and the government officials need to step up and enforce what they are saying,” said Donovan. “When you have children in a school building for six, seven, eight hours a day, we need to provide a level of filtration that is enforced by regulators. If you have a pharmaceutical plant, the FDA will force you to make sure you have the right processes, right environment for manufacturing; it should be the same for schools and office buildings, and I think regulation and enforcement is the only way to make that happen.”

New developments

Room air purifiers

One of the primary outgrowths of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the rise of room air purifiers. “You already see the use of local air cleaners in schools and universities and for home applications,” said Fekkes. “This will not go away but will be expanded.”

With buildings that are not designed to provide enough external air remaining commonplace for the foreseeable future, Adolph said air purifiers provide a viable option going forward. Unfortunately, he said the air purifiers market currently has too many options that are not working correctly. As such, he said it is important that users do a proper analysis of the offers. “It is important to remember that proven technology can be tested and validated with standards and norms,” he said. “On the other hand, in times where there is a search for the silver bullet or snake oil, there will always be someone offering something that does not prove results or tests that do not make absolute sense. We as engineers have an obligation to society to help explain that.”

The use of ozone is an example of one of the “snake oil” solutions Adolph referred to. As the pandemic took hold, air purifiers using ozone to enhance IAQ were being pushed by some. While ozone may be effective in cleaning indoor air in certain situations, it also presents potential health risks to humans exposed to it in large amounts. Other examples of unproven or disproven techniques employed to purify indoor air in the age of COVID-19 include ionization, photocatalytic oxidation and dry hydrogen peroxide.

One of the advantageous features of air purifiers is that they are inherently designed to clean the indoor air. So, where the technology is sound and the systems are properly operated and maintained, Donovan said they can provide a nice complement to the existing HVAC system where necessary. That said, it is important for users to perform due diligence when investing in air purifiers to ensure they are providing the appropriate level of filtration. And he again stressed the threat of off-gassing from common household products that are not easily addressed by HEPA-level air purifiers. “If you’re buying an air purifier, the level of filtration should be clearly stated, because a HEPA filter will not take gases out of the air,” he said.

Ultraviolet technology

Ultraviolet technology is another area of development that has gained some notoriety during the pandemic. And much like air purifiers, it requires the user to have a solid understanding of its capabilities.

One company that has had some level of success employing UV technology in conjunction with HEPA filtration is Lumin-Air out of Indianapolis, Indiana USA. The company has developed a patent-pending system, called Lumin-19, which utilizes a combination of MERV-13 equivalent filtration and UVC to continuously clean and disinfect the air recirculated in mass transit vehicles, such as school busses and public transit vehicles. The company has signed a number of major contracts with school systems and transit authorities in the U.S. to retrofit its technology into existing vehicles.

“You know the jury’s still out on UV, and it looks like perhaps it may work well in parallel with some level of HEPA filtration, but there’s not a lot of data so we probably need more testing to determine its effectiveness,” said Donovan. For this reason, he said there is also a need for standards and regulations to address the new technologies coming to market, such as room air purifiers and UV-based systems. “If we have a standard like an ISO, then we’re all on the same playing field and we’re guaranteeing what we say on the package is actually what’s in the box,” he said.

Sensors

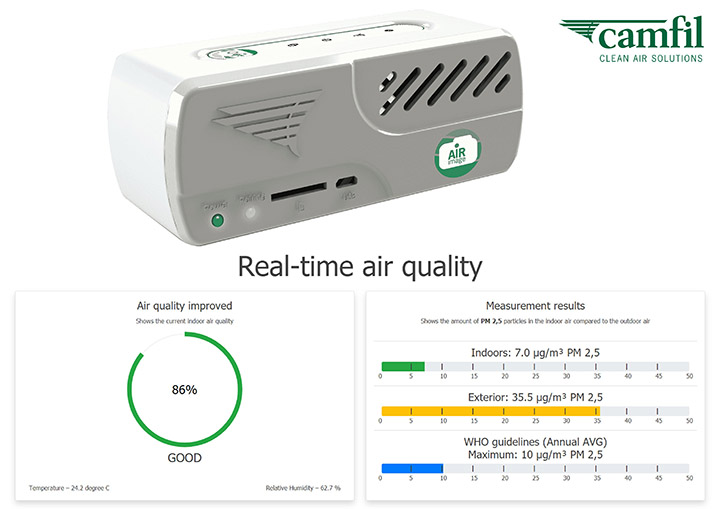

Perhaps the most critical development to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic is in the area of sensor technology – or at least the potential widespread IAQ applications for them.

Donovan said he sees sensor technology playing a key enabling role for IAQ, not just from a transparency perspective for building occupants, but also in making the case for investments in higher –end filtration systems through operational efficiencies.

“Sensors are getting more affordable and can be widely applied,” said Adolph. “They can also be integrated to the internet, giving real-time monitoring data. The nice thing of it is that anyone in the building could have access to IAQ results, which may help in giving confidence to returning employees and customers.”

Donovan said he sees sensor technology playing a key enabling role for IAQ, not just from a transparency perspective for building occupants, but also in making the case for investments in higher –end filtration systems through operational efficiencies.

“You know what, I see the whole sensor technology in the HVAC market kind of exploding,” said Donovan. “And the reason is because HEPA systems are extremely expensive to run, and if there’s nobody in that room, why should we turn them on.”

Donovan said the use of sensor technology can drive efficiencies in total cost of ownership that can help make the case for investments in more advanced levels of filtration. He said an airport during off hours is a good example of where sensors could help eliminate wasted energy. Rather than running the HVAC system 24/7 in an airport, sensors could be employed to cycle the system down during periods of low occupancy, such as during the overnight hours. And during peak hours of occupancy, such as the morning rush, sensors could be used to ramp up the HVAC system, and perhaps engage air purifiers if necessary.

With sensor technology, Donovan said engineers can more effectively make the case for larger up-front investments in higher-end filtration technology by offering evidence of a lower total cost of ownership through more efficient operation of the system over its lifetime.

The future

“We’re now seeing individuals include what’s called ‘Pandemic Mode’ for how their equipment or system should operate,” said Conlan. “Think of it as an emergency generator kicking on when you lose utility power. Well, when we get into a pandemic, how does my HVAC system need to operate differently?”

In a Pandemic-Mode scenario, Conlan said a user can establish certain practices to improve IAQ with the threat of a virus in mind. This could mean adjusting the system to operate with the aim of moving air through a space by raising the temperature set point a degree. Or, a user could switch the fan to “always on” mode, rather than only running when the condensing unit engages to provide cooling or heating. Another option might be lowering the threshold on a demand-controlled ventilation system to bring in more outside air.

“If we think just about air pollution, an office building in Sao Paulo, Mexico City or New York has to get higher classes of filtration to remove the particles compared to cities and facilities in the countryside. Some standards or guidelines would request precisely the same filter in these buildings.”

“As there will always be a balance of what is possible in a retrofit and available options, consultants are looking for unique solutions,” said Adolph “The demand for alternatives is pushing manufacturers to find answers and options. Not directly related to filters, but to air quality, there is also a need to show if the system supplies good air. That opens a new field of air quality monitoring that is affordable and integrated into the installation.”

Fekkes said COVID-19 will force standards worldwide to be reviewed and adjusted to address the possibility of future pandemics.

“There is a massive difference between requirements in countries worldwide if we look into the filtration requirements for commercial, residential and even healthcare institutions,” said Adolph. Western Europe and the Nordic countries have higher requisites related to IAQ and could be a good reference for engineers aiming to be above usual requisites, he said.

In the United States, Adolph said ASHRAE has been able to foster a discussion around IAQ among the general public, which is beginning to drive continuous improvement in what is the minimum requirement in ventilation rates and filtration systems. However, in developing countries, Adolph said there may be standard requirements in place, but enforcement is lacking.

“The main issue I saw with regulations in different countries is that they define a level of filtration as a function of the building type without considering the air contamination,” said Adolph. “If we think just about air pollution, an office building in Sao Paulo, Mexico City or New York has to get higher classes of filtration to remove the particles compared to cities and facilities in the countryside. Some standards or guidelines would request precisely the same filter in these buildings.”

To avoid this, Adolph said Europe started to use DIN EN 16798-3, which requests the use of ISO PM1.0 >50% filters as a minimum for the final filter stage, even in environments with good external air quality. Meanwhile, the ASHRAE Epidemic Taskforce and REHVA (Representatives of European Heating and Ventilation Associations) recommended increasing filtration to at least MERV 13, F7, ISO PM1.0 >50% during the pandemic. The selection of MERV 13 is based on studies that it can reduce infections, is economically viable and is applicable in most buildings. In Europe, it represents the base of design, and in the United States it is likely to be the new trend. Adolph said he expects other countries to follow this trend.

For buildings not designed to provide enough external air to ensure IAQ, air purifiers are an option. Unfortunately, Adolph said the air purifiers industry has too many options that are not working correctly.

Looking ahead, Donovan said he believes the filtration industry has to do a better job of connecting with and educating engineers who are designing buildings. “We need to talk to the engineers to help them understand filtration systems because some of these engineers are doing lighting one day, doing filtration the next day, doing something else the next day, and they need help,” he said.

While there are still challenges ahead for IAQ in what will hopefully soon be the post-COVID-19 era, it is undeniable that the pandemic has brought filtration into the spotlight. Perhaps Fekkes put it best: “It is filtration time.”

References

- “Filters prove effective at reducing airborne viral carriers,” AAF International, 2020.

- “COVID-19 Recommendations for Air Filtration and Ventilation (EMEgEN – 20004.00,” EUROVENT, https://eurovent.eu/?q=articles/covid-19-recommendations-air-filtration-and-ventilation-eme-gen-2000400.

- “Occupational health and safety management — General guidelines for safe working during the COVID-19 pandemic,” ISO, 2020, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:pas:45005:ed-1:v1:en.

- “School Districts Frequently Identified Multiple Building Systems Needing Updates or Replacement,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, June 2020, https://edlabor.house.gov/imo/media/doc/School%20Districts%20Frequently%20Identified%20Multiple%20Building%20Systems%20Needing%20Updates%20or%20Replacement1.pdf.

- “NEA survey finds educators back in classrooms and ready for fall,” National Education Association, June 2021, https://www.nea.org/about-nea/media-center/press-releases/nea-survey-finds-educators-back-classrooms-and-ready-fall.