Deciphering the Decision-Making Process in the Hindsight of Covid-19 Pandemic to Discover IAQ and Clean Air Foresight to Design Cities for Air Quality

It is challenging to advance the cause of air quality in an unstable, unequal, and unsustainable world. Accepting our escalating anthropogenic emissions is alarming for three reasons: it will continue to increase, become a habit, and eventually become irreversible. Outdoors, the inevitable emissions pose a health risk for city inhabitants, requiring global governments to preserve urban air quality. Therefore, good urban air quality governance is imperative since indoor and outdoor air quality are correlated. Left uncontrolled, excessive urban heat and pollutant concentrations demand extensive filtration stages and more effective HVAC equipment to condition the air for pleasant and healthy living.

The emissions from transport and fossil fuel combustion, further exacerbated by rapid urbanization and population growth, have emphasized air quality issues. Cities compete for people, investments, and prosperity; their inhabitants have to compete for clean air to survive. While sustainable urban development aims to design and build cities that provide a low-carbon way to live, clustering inhabitants in polluted cities cannot be celebrated and can negatively impact their well-being.

This is particularly true for people living in dire conditions who rely on opening a window as a form of ventilation simply because they cannot afford or access HVAC and filtration systems. Ultimately, their outdoor and indoor air quality is the same. While enormous funds have been spent in the past decades on energy efficiency, the horrific impact of air quality underfunding came to the forefront with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 to cash its importance. Ultimately, as we strive to ensure better air quality for the built environment, emphasis should also be placed on the equity of clean air delivery irrespective of the socioeconomic status of inhabitants, as clean air should not be a commodity for the elite or the lucky few.

How Bad Are Things?

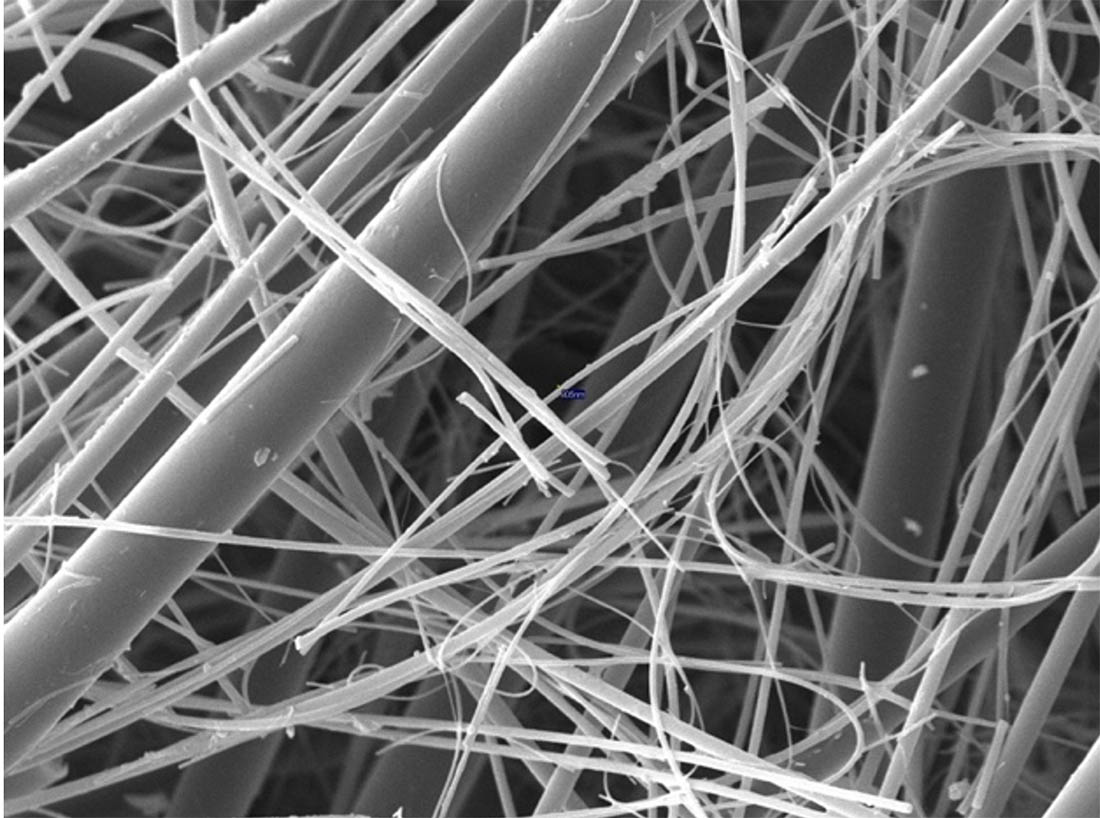

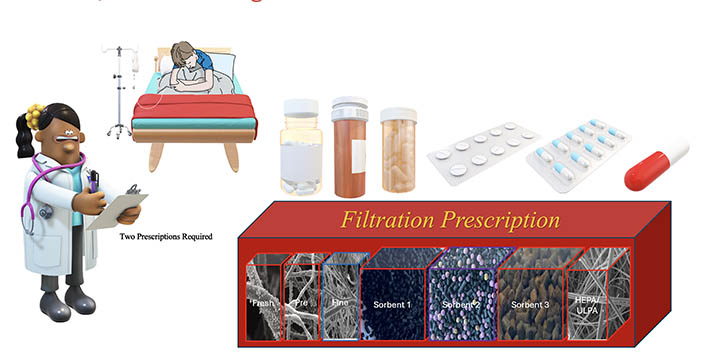

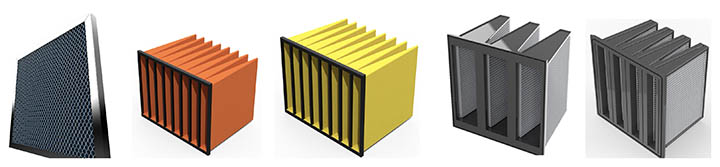

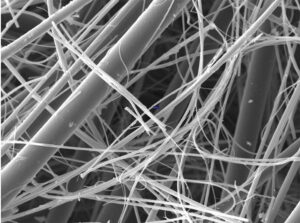

When our family doctor prescribes many types of medication, it is a sign of how sick one is (Figure 1). Equally, when we need to employ extensive filtration stages in HVAC systems (Figure 2), which can be energy-intensive, it reflects how poor our urban air quality is. Our environmental status quo can be best represented by imagining living in an aquarium where the owner adds more fish daily. Space is finite, consumption and waste rates rise, and survival challenges become greater. Eventually, fish get sick and die unless a larger filtration system is installed and the owner buys a bigger aquarium. We do not have the luxury of purchasing a new and bigger planet than the one we already inhabit.

Ultimately, as we strive to ensure better air quality for the built environment, emphasis should also be placed on theequity of clean air delivery irrespective of the socioeconomic status of inhabitants

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The impulsive reactions in dealing with the first COVID-19 wave reflected the fears that the pandemic, which spread like cancer, would take a toll similar to the Spanish flu as the virus spread like cancer. Turning the tide of the pandemic required responding early instead of reacting late to the spark of the virus, which spread as a result of the employment of ineffective processes. For our cities to be safe to inhabit, it is critical to foster unconventional and holistic approaches orchestrating big air quality data and AI-based engines’ intelligence to respond adaptively and effectively to any variation in IAQ and human occupancy.

The pandemic has demonstrated that although we had the technologies and processes to reduce virus transmission, we needed to ask different air quality questions. The contested meaning of clean air, rival filtration formulations, and inconsistent performance of conventional ventilation systems form a dissuasive IAQ foundation for healthy living. While we may innately know the general importance of clean air, embedding the required HVAC and filtration technologies from Day One is critical to attaining higher air quality targets. Therefore, investing in continuous air quality monitoring infrastructures and filter performance is central for optimal clean air outcomes.

Finding the best strategy to respond to the spread of the virus during the pandemic was challenging. The developments of the pandemic were surrounded by risk and uncertainty. A key lesson from the pandemic is recognizing the need to establish decision-making mechanisms that foster resilience and aim toward sustainable and healthy cities based on humancentric approaches. Making decisions under risk suggests the possible outcomes are known. The intensity of the pandemic and impact on global economies sparked doubts about the means-to-end notion of the decision-making process and emphasized the importance of clean air.

The attention air quality received during the pandemic soon was overshadowed, as other priorities, such as energy efficiency, emerged. Overlooking the importance of inhaling clean air and its relation to our well-being suggests that air quality was waiting for the pandemic to showcase its critical role. Admittedly, degradation in air filtration and ventilation system performances have made our built-environment easy prey for pandemic conditions. For decision-makers to entertain raising the bar of the health and safety of their buildings, they insist on basing their approval on the economics and financial gains of filtration upgrades alongside required retrofitting works. Ultimately, focusing only on the capital expenditure of filtration upgrades thwarts any air quality enhancements and overlooks their impact on occupants’ well-being and productivity. Air quality should be granted a seat at the HVAC table and a voice in the building design strategies rather than waiting for the next pandemic to bring it to the spotlight.

Air Quality Governance

Urban air quality governance emerged as a central realignment to protect our built environment, well-being, and economic vitality. Although met with cynicism, enshrining air quality policies holds immense promise to drive change toward healthy building designs beyond conventional settings. It is time to challenge and change how building envelopes and ventilation systems are designed, operated, and maintained to stand firm against any deterioration in air quality. Optimizing ventilation quantities and admission schemes must entail responding to the concentrations of other airborne pollutants aside from particulate matter, such as gaseous pollutants and bioaerosols. Inhaling indoor air that is efficiently conditioned, appropriately filtered, and adequately ventilated constitutes the essence of sustainable living in a healthy building where our well-being is protected.

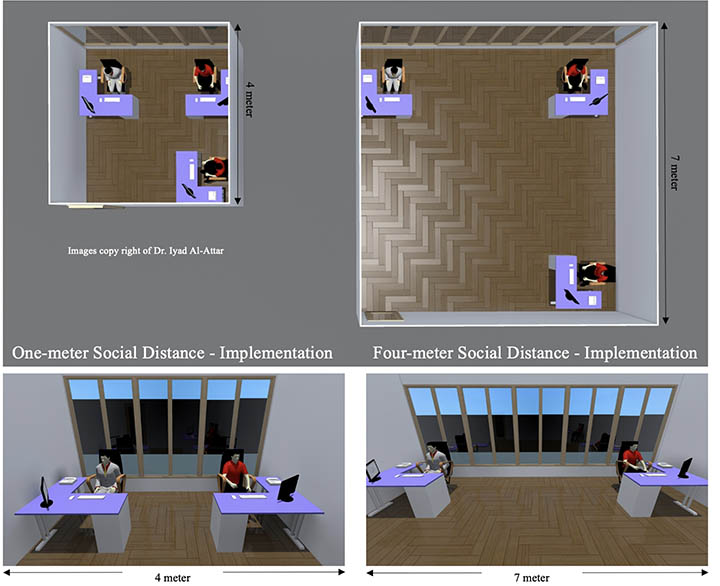

Although higher ventilation rates per person or area alongside upgraded filtration efficiency are logical solutions, occupied envelopes with dense human occupancy and close proximity are challenging to predict. Therefore, systems such as demand-controlled ventilation stand out as an effective adaptive strategy to variations in CO2 concentrations. Energy-efficient ventilation systems focusing on air quality are paramount when responding to the increase or decrease in human occupancy indicated by CO2 levels. As social distancing was the hype during the pandemic (Figure 3), its implementation to alter the pre-pandemic human occupancy in offices, schools, or shopping malls seems impractical due to the reduced use of the occupiable building space. Ultimately, advanced and adaptive ventilation and filtration technologies can be central in ensuring appropriate levels of human occupation.

We seek refuge in our buildings and aspire to healthy living and working conditions that protect our well-being. The allure of living in smart cities must include embracing data-driven strategies to align building urban resilience with enhanced air quality. The ties of targets among air quality, thermal comfort, and ventilation rates make accessing, employing, and integrating HVAC and air filtration technologies essential to embracing sustainable built environments. Relying solely on frequent replacement and dicey upgrades of air filters cannot be accepted if one opts for sustainable living and empowered circular economies.

Abandoning our buildings during the pandemic meant they were not fit to occupy. Although locking down cities seemed rational, it may not have been right. Humanity has borne the heaviest burden during the last pandemic, with economic paralysis stretched beyond lives lost. School closures caused an unprecedented disruption and impacted 94% of students worldwide, putting close to 1.6 billion children and youth out of school by April 2020[1,2]. The pandemic forced students to abandon their classrooms, which is nearly a declaration that their indoor space is thought to be occupied by SARS-CoV-2 and, therefore, unfit for healthy educational purposes.

It is naive to believe that pandemics like COVID-19 are once-in-a-generation events. Although no one questions the intent of attempting to defeat the pandemic, what ailed our approach was the late response to induce immediate changes rather than the employment of ready-to-go regulations engineered to prevent pandemics. After the first wave struck, experts started tweaking standards, investigating existing ventilation rates, and upgrading installed filter efficiency. Looking back at the number of COVID-19 waves, one can say that the virus only left our cities when it infected all of us.

The Role of Governments

Governments must legislate air quality policies to avoid having cities become catalysts for virus transmission. Striving for clean and green cities requires widening the scope to include “air quality” in modern urban planning and the healthy buildings we claim to design. The fluctuating interest of governments in air quality driven by pandemics and wildfires forced the authorities to pull the plug on cities by enforcing curfews and lockdowns to reduce exposure to pollutants and bioaerosols. While the success of such measures is subjective, their impact in reducing virus transmission remains debatable. Shallow victories of mandating masks and vaccines misled us to believe that pandemics are poised for defeat. This is a wake-up call to diverge from the norm and progress toward clear thinking of what healthy buildings and cities are all about and how maintaining and sustaining their readiness is the order of the day. The initial rejection of out-of-the-box air quality (Figure 4) and adaptive HVAC approaches should not threaten us with scorn and dread to transcend our cities to be pandemic-proof. Fumbling the future of air quality by drafting new blueprints for HVAC, filtration, and IAQ guidelines every time a pandemic invades our cities may put out the pandemic flames, but not their fires.

The Overarching Message of Air Quality

The importance of clean air must be at the heart of every building we occupy. Enhancing air quality is achievable if the available technologies and innovations are employed for energy-efficient operation. The determination that built empires can certainly orchestrate air quality infrastructure and second-to-none human-centric HVAC systems.

However, relying on symbolic forces of clean air and appealing to the ethical compass of decision-makers and operators cannot ensure sustainable indoor air quality. When building operators are legally bound to sustainably deliver clear air, they will get to the core of building problems and provide optimum – not just acceptable – indoor air quality. It is time to strive for sustainable cities, resilient environments, and a building envelope designed, built, and operated according to the highest standards of performance excellence (Figure 5). That requires ventilation and filtration systems that work smarter, think faster, and respond earlier to any variation in air quality. Before relying on conventional air quality advice, we should question whether the “IAQ” lens regards “clean air” as a right or delight for human occupants. As we aspire to a modern and sustainable built environment, raising the bar of air quality is imperative in shaping the future of our cities to evolve as an equitable, responsible, and just society.