What (Filtration) Lessons Aren’t We Learning?

Air quality is crucial for urban sustainability, affecting public health, the environment, and the economy. Managing air quality has become a significant challenge for cities due to increasing urbanization and industrial activities. The recent pandemic has highlighted the importance of Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) for built environments and building envelopes. Safeguarding the well-being of human occupants is essential for sustainable and healthy living in buildings. Therefore, incorporating air quality considerations from the beginning of any sustainable urban development is crucial for designers and occupants. To ensure fresh and clean air delivery to building envelopes, governance must be established using available technologies in HVAC, filtration, and air quality monitoring. Governing IAQ involves policies, regulations, and strategies designed to monitor and manage pollutants’ existence and concentration indoors.

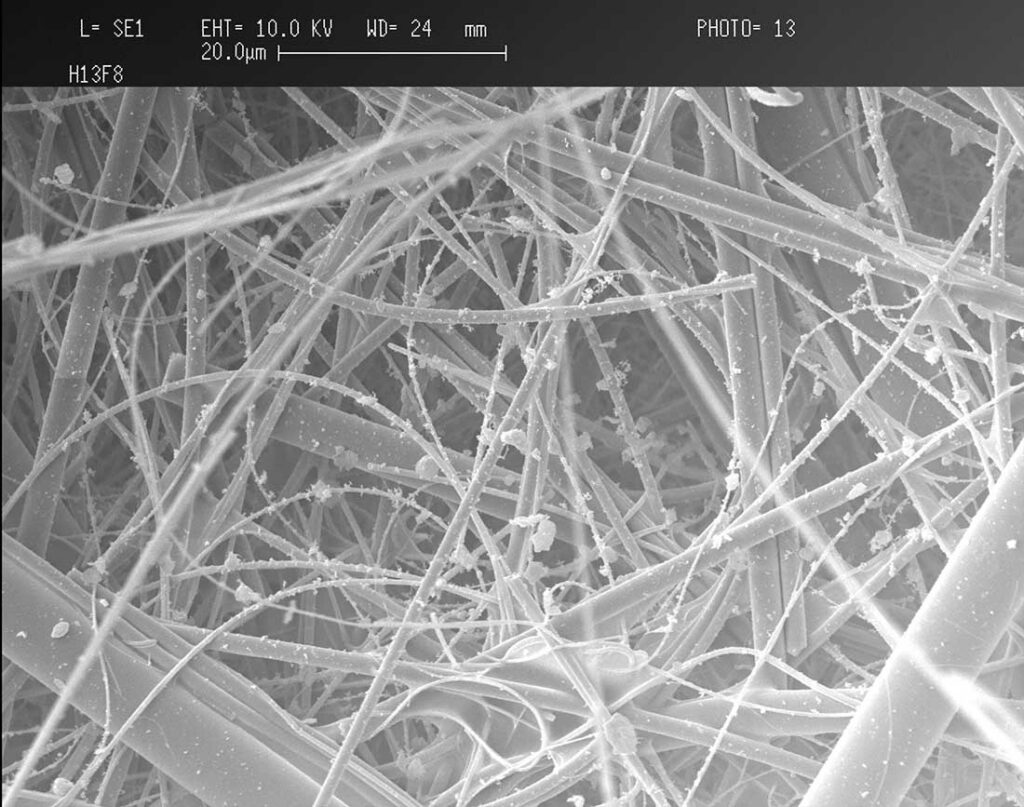

The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the importance of IAQ in public health, highlighting the crucial role of filtration technologies in maintaining healthy indoor environments. As the airborne transmission of pathogens became a primary concern, advanced filtration systems gained prominence for their effectiveness in removing ultrafine particles, biological contaminants, and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). The pandemic sent a clear message that a strategy is needed to investigate the capabilities of existing filtration systems in capturing all types of pollutants and protecting human health and well-being.

Poor IAQ has a significant impact on public health due to inconsistent adherence to standards, lack of awareness, and legislation that does not deal with the root causes of poor IAQ. Air quality governance emphasizes the importance of protecting the well-being of city dwellers and occupants from various health issues, such as respiratory diseases and cardiovascular conditions. Obviously, protection comes to the forefront when considering the transmission of airborne viruses such as Corona. An increase in medical care and hospitalization represents a substantial cost for governments to accommodate the increased demand for such services. Research has shown that improving IAQ can lead to fewer respiratory issues, decreased asthma rates, and reduced absenteeism in schools and workplaces1. When cities make their built environments healthy and safe, they can reduce health-related costs and re-allocate resources to promote economic growth.

Sufficient evidence succinctly highlights the critical need to regulate IAQ through codes and standards and through their professional implementation and compliance2. This can be done by appropriate ventilation, efficient filtration, and contaminant control. Air quality governance can facilitate an implementation platform to reduce the concentration of harmful pollutants, aiming to avoid their accumulation on HVAC equipment, ducts, and the indoor environment. Governance frameworks help set limits on these pollutants, ensuring that building designs, HVAC systems, and ventilation practices adhere to standards that maintain safe indoor environments.

The pandemic has presented new challenges for filtration technologies, HVAC equipment, and building standards for which they were unprepared. It has highlighted the need to adapt practices to fully realize the benefits of technologies and standards for enhanced IAQ. We live in a fortunate era. Decades ago, minimal technology existed in buildings, limited to public telecommunications utility and a pneumatic control system for the HVAC system. Today, technologies influence the design of the built environment where automated processes automatically control buildings’ operations including HVAC, lighting, security, and other systems. Technologies will continue to drive innovations in building design, construction and operation in the future, and certainly in the way we manage and control IAQ.

It is essential to note that individual behaviors play a significant role in developing respiratory issues and incurring healthcare costs compared to the quality of the built environments. Social change through public awareness, education, and community engagement is not just important but also essential. It is the key to bridging the gaps between legislation and implementing HVAC, filtration, and building standards governing IAQ.

While IAQ gained significant attention during the pandemic, it did not fully define buildings or constitute a common dominator in the grand scheme of building safety metrics. Achieving optimal ventilation rates, filter selection and configuration is difficult due to the dynamic nature of living and working in buildings, as simulating these dynamics is rather complex. The demand for fresh, clean, and sustainable air has led to new building standards for ventilation and filtration. However, we must acknowledge that we have yet to tailor ventilation rates, filtration efficiencies, and configuration for each application. There is a great deal to learn, particularly when addressing the reliance on conventional maintenance measures and simply committing to meeting the thermal comfort commitments. To enhance our health and well-being, we need individuals who can think systematically and grasp the essential IAQ initiatives and concepts connected to the operation of buildings as integrated systems. By giving precedence to IAQ, we can position HVAC and filtration systems to adjust to fluctuations in air quality driven by data-informed feedback loops of indoor pollutant concentrations.

A primary challenge in advancing air quality governance is the fragmentation of authority between local, national, and international bodies. Each level of governance may have different priorities and resources, leading to inconsistencies in implementing air quality standards. Additionally, there is often a need for more public awareness regarding the importance of IAQ in virus transmission. As a result, regulatory bodies face challenges in enforcing policies that require costly upgrades to infrastructure, such as

retrofitting HVAC systems in schools and office buildings. Financial institutions can play a role in funding the retrofits necessary for building owners to undertake their IAQ obligation, where governments can monitor the IAQ outcomes afterward.

Moreover, standardization of measurement protocols is critical. While multiple studies underscore the need for improved IAQ3,4 the lack of standardized methods to measure viral particles in the air complicates enforcement. Governance frameworks should address these deficiencies by establishing universally accepted IAQ metrics and monitoring technologies that enable real-time air quality assessment in enclosed environments. Clearly and most importantly, no one can enhance IAQ without characterizing airborne pollutants’ physical and chemical characteristics. Moreover, continuous and reliable air quality monitoring sets the stage for a future outlook of buildings beyond thermal comfort, particle capture, and a simple thermostat displaying current ambient temperature.

The governance of air quality has significant socioeconomic implications. Implementing strong IAQ regulations often requires substantial investment in infrastructure upgrades, especially for small businesses and public institutions. However, the long-term economic benefits of reducing viral transmission, minimizing healthcare costs, and ensuring public safety far outweigh the initial expenses. Studies, such as those by Milton et al. and Wang et al.5,6 suggest that improved IAQ can lead to lower absenteeism, enhanced productivity, and cognitive function. Therefore, governments must balance short-term financial considerations with the long-term benefits of reducing the transmission of airborne pathogens.

Investing in air quality governance leads to healthier living and working environments and supports broader societal and environmental goals. These goals revolve around enhancing public health by reducing respiratory diseases and virus transmission while maintaining energy-efficient operations by integrating smart HVAC systems and IAQ initiatives. Ultimately, air quality governance can help ensure equitable access to clean indoor air, especially for vulnerable populations, and safeguard their health and well-being. However, it is essential to note that individual behaviors play a significant role in developing respiratory issues and incurring healthcare costs compared to the quality of the built environments. Social change through public awareness, education, and community engagement is not just important but also essential. It is the key to bridging the gaps between legislation and implementing HVAC, filtration, and building standards governing IAQ. This emphasis on public awareness and education should make all feel empowered and integral to reaching the desired IAQ outcomes.

Controlling IAQ in places like schools and hospitals can be challenging due to the simultaneous impact and exposure of multiple parameters and the influx of visitors. Managing IAQ can be complicated due to its dependency on various factors, such as the coexistence of particulates, gases, and bioaerosols, some of which are difficult to measure. Furthermore, fluctuating human occupancy indicated by carbon dioxide present in the building envelope emphasizes the need for demand-controlled ventilation systems, which are also intertwined with filtration systems. Additionally, the transient performance of air filters and their premature clogging further complicates the maintenance of IAQ. Inconsistent air quality throughout the year, particularly in buildings without standardized regulations, and especially those that sustain massive infiltration leave occupants vulnerable to poor IAQ and accelerating the aging of facilities, including HVAC equipment and systems.

Air quality governance also addresses environmental impacts. Ensuring air quality regulations align with sustainability and climate goals promotes the use of low-emission building materials, reduces reliance on energy-intensive ventilation systems, and encourages the attainment of green building certifications. By managing indoor air quality to complement environmental objectives, governance frameworks can contribute to more sustainable urban development and help combat climate change by reducing carbon footprints.

Governance is expected to play an increasingly significant role in safeguarding the well-being of city dwellers and occupants. The benefits of improved IAQ will likely drive the implementation of more stringent regulations relevant to employing appropriate ventilation, efficient filtration, and contaminant control. However, social change is imperative to realize the fullest potential of current technologies, as smart buildings require responsible users to interact with the indoor environment. Therefore, we need to sharpen our tools and make the most of available technologies to achieve this.

As Abraham Lincoln suggested, “If I had eight hours to chop down a tree, I would spend the first six of them sharpening my axe.” Air quality governance requires dedicated professionals and an informed community ready to diligently work toward providing sustainable, fresh, and clean air.

References:

- Niza, I.L., de Souza, M.P., da Luz, I.M. and Broday, E.E., 2024. Sick building syndrome and its impacts on health, well-being and productivity: A systematic literature review. Indoor and Built Environment, 33(2), pp.218-236.

- Morawska, L., Allen, J., Bahnfleth, W., Bennett, B., Bluyssen, P.M., Boerstra, A., Buonanno, G., Cao, J., Dancer, S.J., Floto, A. and Franchimon, F., 2024. Mandating indoor air quality for public buildings. Science, 383(6690), pp.1418-1420.

Huang, J., 2023. Developing Disinfection Strategies for Controlling Human Norovirus Sars-Cov-2 and - Clostridioides Difficile Endospores in Long-Term Care Facilities (Doctoral dissertation, Clemson University).

- Alegbeleye, B.J., Akpoveso, O.O.P. and Mohammed, R.K., 2020. Coronavirus disease-19 outbreak: barriers to hand hygiene practices among healthcare professionals in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Sci Adv, 1(1).

- Milton D.K., Glencross P.M., & Walters M.D. (2000). “Risk of sick leave associated with outdoor air supply rate, humidification, and occupant complaints.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

- Wang, C.C., Prather, K.A., Sznitman, J., Jimenez, J.L., Lakdawala, S.S., Tufekci, Z. and Marr, L.C., 2021. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science, 373(6558), p.eabd9149.